- Home

- Charles Reade

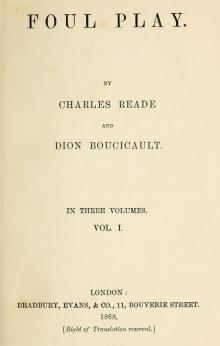

Foul Play

Foul Play Read online

Produced by James Rusk. HTML version by Al Haines.

[Transcriber's note: Italics are indicated by theunderscore character (_). Accent marks are ignored.]

FOUL PLAY.

by

Charles Reade and Dion Boucicault

CHAPTER I.

THERE are places which appear, at first sight, inaccessible to romance;and such a place was Mr. Wardlaw's dining-room in Russell Square. It wasvery large, had sickly green walls, picked out with aldermen, fulllength; heavy maroon curtains; mahogany chairs; a turkey carpet an inchthick: and was lighted with wax candles only.

In the center, bristling and gleaming with silver and glass, was a roundtable, at which fourteen could have dined comfortably; and at oppositesides of this table sat two gentlemen, who looked as neat, grave,precise, and unromantic, as the place: Merchant Wardlaw, and his son.

Wardlaw senior was an elderly man, tall, thin, iron-gray, with a roundhead, a short, thick neck, a good, brown eye, a square jowl thatbetokened resolution, and a complexion so sallow as to be almostcadaverous. Hard as iron: but a certain stiff dignity and respectabilitysat upon him, and became him.

Arthur Wardlaw resembled his father in figure, but his mother in face. Hehad, and has, hay-colored hair, a forehead singularly white and delicate,pale blue eyes, largish ears, finely chiseled features, the under lipmuch shorter than the upper; his chin oval and pretty, but somewhatreceding; his complexion beautiful. In short, what nineteen people out oftwenty would call a handsome young man, and think they had described him.

Both the Wardlaws were in full dress, according to the invariable customof the house; and sat in a dead silence, that seemed natural to the greatsober room.

This, however, was not for want of a topic; on the contrary, they had amatter of great importance to discuss, and in fact this was why theydined _tete-a-tete._ But their tongues were tied for the present; in thefirst place, there stood in the middle of the table an epergne, the sizeof a Putney laurel-tree; neither Wardlaw could well see the other,without craning out his neck like a rifleman from behind his tree; andthen there were three live suppressors of confidential intercourse, twogorgeous footmen and a somber, sublime, and, in one word, episcopal,butler; all three went about as softly as cats after a robin, andconjured one plate away, and smoothly insinuated another, and seemedmodels of grave discretion: but were known to be all ears, and bound by asecret oath to carry down each crumb of dialogue to the servants' hall,for curious dissection and boisterous ridicule.

At last, however, those three smug hypocrites retired, and, by good luck,transferred their suffocating epergne to the sideboard; so then fatherand son looked at one another with that conscious air which naturallyprecedes a topic of interest; and Wardlaw senior invited his son to try acertain decanter of rare old port, by way of preliminary.

While the young man fills his glass, hurl we in his antecedents.

At school till fifteen, and then clerk in his father's office tilltwenty-two, and showed an aptitude so remarkable, that John Wardlaw, whowas getting tired, determined, sooner or later, to put the reins ofgovernment into his hands. But he conceived a desire that the future headof his office should be a university man. So he announced his resolution,and to Oxford went young Wardlaw, though he had not looked at Greek orLatin for seven years. He was, however, furnished with a private tutor,under whom he recovered lost ground rapidly. The Reverend Robert Penfoldwas a first-class man, and had the gift of teaching. The house of Wardlawhad peculiar claims on him, for he was the son of old Michael Penfold,Wardlaw's cashier; he learned from young Wardlaw the stake he was playingfor, and instead of merely giving him one hour's lecture per day, as hedid to his other pupils, he used to come to his rooms at all hours, andforce him to read, by reading with him. He also stood his friend in aserious emergency. Young Wardlaw, you must know, was blessed or cursedwith Mimicry; his powers in that way really seemed to have no limit, forhe could imitate any sound you liked with his voice, and any form withhis pen or pencil. Now, we promise you, he was one man under his father'seye, and another down at Oxford; so, one night, this gentleman, beingwarm with wine, opens his window, and, seeing a group of undergraduateschattering and smoking in the quadrangle, imitates the peculiar gratingtones of Mr. Champion, vice-president of the college, and gives themvarious reasons why they ought to disperse to their rooms and study."But, perhaps," says he, in conclusion, "you are too blind drunk to readBosh in crooked letters by candle-light? In that case----"

And he then gave them some very naughty advice how to pass the evening;still in the exact tones of Mr. Champion, who was a very, very strictmoralist; and this unexpected sally of wit caused shrieks of laughter,and mightily tickled all the hearers, except Champion ipse, who waslistening and disapproving at another window. He complained to thepresident. Then the ingenious Wardlaw, not having come down to us in adirect line from Bayard, committed a great mistake--he denied it.

It was brought home to him, and the president, who had laughed in hissleeve at the practical joke, looked very grave at the falsehood;Rustication was talked of and even Expulsion. Then Wardlaw camesorrowfully to Penfold, and said to him, "I must have been awfully cut,for I don't remember all that; I had been wining at Christchurch. I doremember slanging the fellows, but how can I tell what I said? I say, oldfellow, it will be a bad job for me if they expel me, or even rusticateme; my father will never forgive me; I shall be his clerk, but never hispartner; and then he will find out what a lot I owe down here. I'm donefor! I'm done for!"

Penfold uttered not a word, but grasped his hand, and went off to thepresident, and said his pupil had wined at Christchurch, and could not beexpected to remember minutely. Mimicry was, unfortunately, a habit withhim. He then pleaded for the milder construction with such zeal andeloquence that the high-minded scholar he was addressing admitted thatconstruction was _possible,_ and therefore must be received. So theaffair ended in a written apology to Mr. Champion which had all thesmoothness and neatness of a merchant's letter. Arthur Wardlaw wasalready a master in that style.

Six months after this, and one fortnight before the actual commencementof our tale, Arthur Wardlaw, well crammed by Penfold, went up for hisfinal examination, throbbing with anxiety. He passed; and was so gratefulto his tutor that, when the advowson of a small living near Oxford cameinto the market, he asked Wardlaw senior to lend Robert Penfold a sum ofmoney, much more than was needed. And Wardlaw senior declined without amoment's hesitation.

This slight sketch will serve as a key to the dialogue it has postponed,and to subsequent incidents.

"Well, Arthur, and so you have really taken your degree?"

"No, sir; but I have passed my examination. The degree follows as amatter of course--that is a mere question of fees."

"Oh! Then now I have something to say to you. Try one more glass of the'47 port. Stop; you'll excuse me; I am a man of business; I don't doubtyour word; Heaven forbid! but, do you happen to have any document you canproduce, in further confirmation of what you state; namely, that you havepassed your final examination at the University?"

"Certainly, sir;" replied young Wardlaw. "My Testamur."

"What is that?"

The young gentleman put his hand in his pocket and produced his Testamur,or "We bear witness"; a short printed document in Latin, which may bethus translated:

"We bear witness that Arthur Wardlaw, of St. Luke's College, has answeredour questions in humane letters.

"GEORGE RICHARDSON, "ARTHUR SMYTHE, "EDWARD MERIVALE, _"Examiners."_

Wardlaw senior took it, laid it beside him on the table, inspected itwith his double eye-glass, and, not knowing a word of Latin, was mightilyimpressed, and his respect for his son rose forty or forty-five per cent.

"Very well, sir," said he. "Now listen to me. Pe

rhaps it was an old man'sfancy; but I have often seen in the world what a stamp these universitiesput upon a man. To send you back from commerce to Latin and Greek, attwo-and-twenty, was trying you rather hard; it was trying you doubly;your obedience, and your ability into the bargain. Well, sir, you havestood the trial, and I am proud of you. And so now it is my turn. Fromthis day and from this hour look on yourself as my partner in the oldestablished house of Wardlaw. My balance-sheet shall be preparedimmediately, and the partnership deed drawn. You will enter on aflourishing concern, sir; and you will virtually conduct it, in writtencommunication with me; for I have had five-and-forty years of it; andthen my liver, you know! Watson advises me strongly to leave my desk, andtry country air, and rest from business and its cares."

He paused a moment; and the young man drew a long breath, like one whowas in the act of being relieved of some terrible weight.

As for the old gentleman, he was not observing his son just then, butthinking of his own career; a certain expression of pain and regret cameover his features; but he shook it off with manly dignity. "Come, come,"said he, "this is the law of Nature, and must be submitted to with a goodgrace. Wardlaw junior, fill your glass." At the same time he stood up andsaid, stoutly, "The setting sun drinks to the rising sun;" but could notmaintain that artificial style, and ended with, "God bless you, my boy,and may you stick to business; avoid speculation, as I have done; and sohand the concern down healthy to your son, as my father there (pointingto a picture) handed it down to me, and I to you."

His voice wavered slightly in uttering this benediction; but only for amoment. He then sat quietly down, and sipped his wine composedly.

Not so the other. His color came and went violently all the time hisfather was speaking, and, when he ceased, he sank into his chair withanother sigh deeper than the last, and two half-hysterical tears came tohis pale eyes.

But presently, feeling he was expected to say something, he struggledagainst all this mysterious emotion, and faltered out that he should notfear the responsibility, if he might have constant recourse to his fatherfor advice.

"Why, of course," was the reply. "My country house is but a mile from thestation. You can telegraph for me in any case of importance."

"When would you wish me to commence my new duties?"

"Let me see, it will take six weeks to prepare a balance-sheet, such as Icould be content to submit to an incoming partner. Say two months."

Young Wardlaw's countenance fell.

"Meantime you shall travel on the Continent and enjoy yourself."

"Thank you," said young Wardlaw, mechanically, and fell into a brownstudy.

The room now returned to what seemed its natural state. And its silencecontinued until it was broken from without.

A sharp knocking was heard at the street door, and resounded across themarble hall.

The Wardlaws looked at one another in some little surprise.

"I have invited nobody," said the elder. Some time elapsed, and then afootman made his appearance and brought in a card.

"Mr. Christopher Adams."

Now that Mr. Christopher Adams should call on John Wardlaw, in hisprivate room, at nine o'clock in the evening, seemed to that merchantirregular, presumptuous and monstrous. "Tell him he will find me at myplace of business to-morrow, as usual," said he, knitting his brows.

The footman went off with this message; and, soon after, raised voiceswere heard in the hall, and the episcopal butler entered the room with aninjured countenance.

"He says he _must_ see you; he is in great anxiety."

"Yes, I am in great anxiety," said a quavering voice at his, elbow; andMr. Adams actually pushed by the butler, and stood, hat in hand, in thosesacred precincts. "'Pray excuse me, sir," said he, "but it is veryserious; I can't be easy in my mind till I have put you a question."

"This is very extraordinary conduct, sir," said Mr. Wardlaw. "Do youthink I do business here, and at all hours?"

"Oh, no, sir. It is my own business. I am come to ask you a very seriousquestion. I couldn't wait till morning with such a doubt on my mind."

"Well, sir, I repeat this is irregular and extraordinary; but as you arehere, pray what is the matter?" He then dismissed the lingering butlerwith a look. Mr. Adams cast uneasy glances on young Wardlaw.

"Oh," said the elder, "you can speak before him. This is my partner; thatis to say, he will be as soon as the balance-sheet can be prepared andthe deed drawn. Wardlaw junior, this is Mr. Adams, a very respectablebill discounter."

The two men bowed to each other, and Arthur Wardlaw sat down motionless.

"Sir, did you draw a note of hand to-day?" inquired Adams of the eldermerchant.

"I dare say I did. Did you discount one signed by me?"

"Yes, sir, we did."

"Well, sir, you have only to present it at maturity. Wardlaw & Son willprovide for it, I dare say." This with the lofty nonchalance of a richman who had never broken an engagement in his life.

"Ah, that I know they will if it is all right; but suppose it is not?"

"What d'ye mean?" asked Wardlaw, with some astonishment.

"Oh, nothing, sir! It bears your signature, that is good for twenty timesthe amount; and it is indorsed by your cashier. Only what makes me alittle uneasy, your bills used to be always on your own forms, and so Itold my partner; he discounted it. Gentlemen, I wish you would just lookat it."

"Of course we will look at it. Show it Arthur first; his eyes are youngerthan mine."

Mr. Adams took out a large bill-book, extracted the note of hand, andpassed it across the table to Wardlaw junior. He took it up with a sortof shiver, and bent his head very low over it; then handed it back insilence.

Adams took it to Wardlaw senior and laid it before him by the side ofArthur's Testamur.

The merchant inspected it with his glasses.

"The writing is mine, apparently."

"I am very glad of it," said the bill-broker, eagerly.

"Stop a bit," said Mr. Wardlaw. "Why, what is this? For two thousandpounds! and, as you say, not my form. I have signed no note for twothousand pounds this week. Dated yesterday. You have not cashed it, Ihope?"

"I am sorry to say my partner has."

"Well, sir, not to keep you in suspense, the thing is not worth the stampit is written on."

"Mr. Wardlaw!--Sir!--Good heavens! Then it is as I feared. It is aforgery."

"I should be puzzled to find any other name for it. You need not look sopale, Arthur. We can't help some clever scoundrel imitating our hands;and as for you, Adams, you ought to have been more cautious."

"But, sir, your cashier's name is Penfold," faltered the holder, clingingto a straw. "May he not have drawn--is the indorsement forged as well?"

Mr. Wardlaw examined the back of the bill, and looked puzzled. "No," saidhe. "My cashier's name is Michael Penfold, but this is indorsed 'RobertPenfold.' Do you hear, Arthur? Why, what is the matter with you? You looklike a ghost. I say there is your tutor's name at the back of this forgednote. That is very strange. Just look, and tell me who wrote these twowords 'Robert Penfold'?"

Young Wardlaw took the document and tried to examine it calmly, but itshook visibly in his hand, and a cold moisture gathered on his brow. Hispale eyes roved to and fro in a very remarkable way; and he was so longbefore he said anything that both the other persons present began to eyehim with wonder.

At last he faltered out, "This 'Robert Penfold' seems to me very like hisown handwriting. But then the rest of the writing is equally like yours,sir. I am sure Robert Penfold never did anything wrong. Mr. Adams, pleaseoblige _me._ Let this go no further till I have seen him, and asked himwhether he indorsed it."

"Now don't you be in a hurry," said the elder Wardlaw. "The firstquestion is, who received the money?"

Mr. Adams replied that it was a respectable-looking man, a youngclergyman.

"Ah!" said Wardlaw, with a world of meaning.

"Father!" said young Wardlaw, imploringly, "for my sake, sa

y no moreto-night. Robert Penfold is incapable of a dishonest act."

"It becomes your years to think so, young man. But I have lived longenough to see what crimes respectable men are betrayed into in the hourof temptation. And, now I think of it, this Robert Penfold is in want ofmoney. Did he not ask me for a loan of two thousand pounds? Was not thatthe very sum? Can't you answer me? Why, the application came throughyou."

Receiving no reply from his son, but a sort of agonized stare, he tookout his pencil and wrote down Robert Penfold's address. This he handedthe bill-broker, and gave him some advice in a whisper, which Mr.Christopher Adams received with a profusion of thanks, and bustled away,leaving Wardlaw senior excited and indignant, Wardlaw junior ghastly paleand almost stupefied.

Scarcely a word was spoken for some minutes, and then the younger manbroke out suddenly: "Robert Penfold is the best friend I ever had; Ishould have been expelled but for him, and I should never have earnedthat Testamur but for him."

The old merchant interrupted him. "You exaggerate. But, to tell thetruth, I am sorry now I did not lend him the money you asked for. For,mark my words, in a moment of temptation that miserable young man hasforged my name, and will be convicted of the felony and punishedaccordingly."

"No, no. Oh, God forbid!" shrieked young Wardlaw. "I couldn't bear it. Ifhe did, he must have intended to replace it. I must see him; I will seehim directly." He got up all in a hurry, and was going to Penfold to warnhim, and get him out of the way till the money should be replaced. Buthis father started up at the same moment and forbade him, in accents thathe had never yet been able to resist.

"Sit down, sir, this instant," said the old man, with terrible sternness."Sit down, I say, or you will never be a partner of mine. Justice musttake its course. What business and what right have we to protect a felon?I would not take your part if you were one. Indeed it is too late now,for the detectives will be with him before you could reach him. I gaveAdams his address."

At this last piece of information Wardlaw junior leaned his head on thetable and groaned aloud, and a cold perspiration gathered in beads uponhis white forehead.

The Cloister and the Hearth: A Tale of the Middle Ages

The Cloister and the Hearth: A Tale of the Middle Ages Foul Play

Foul Play Peg Woffington

Peg Woffington White Lies

White Lies